[FKPXLS] VOL.44 / The pixel making of an American Dream

I felt like I have traveled from another dimension, so present, yet invisible. I felt like I was never a part of this tranquil and idyllic beauty.

The brilliant Can Duruk wrote a timely piece on how software is not only eating the world but cannibalistically eating itself:

We are coming to a point where software is developing so fast and the abstractions are getting better that soon we will have more software written by a smaller number of people. In other words, just like software made legions of people working in other industries obsolete, it will soon make its creators less valuable too. In short, software will eat software. Or maybe, software will eat software people?

On a similar note, Technically’s Justin Gage wrote about the rise of JAMstack as a new paradigm for building sites and apps, “couching complexity behind well-designed APIs that make actual deployment easy”. The next logical step is outsourcing those APIs, and it will become an increasingly common piece of how developers automate parts of their work.

I still remember taking on my first design client five years ago, when I was still a freshman in college. Fake it til you make it. I’d remind myself as I nervously tried to export the pixels in the correct dimension on Adobe Illustrator. I was hanging out with a group of designers who were a few years older and have gotten offers the likes of Facebook and Google. I still remember how they were the only people I knew who had websites that looked like magazines and domains of their own names.

They are the coolest people I know and taught me everything about design tools and creative programming. I still remember I marveled at the simplicity of Sketch, the power of Javascript to animate a vision, and the competency of FramerJS to alchemize static pixels with realtime JSON data to make everything look real.

Many sleepless nights were spent simulate realities with pixels, and hence the origins of the name Fakepixels. “Are you Fakepixels?” a guy I never met before came up to me at a frat party, slurring, “didn’t know you were a real person.” I was a rare guest at late parties and usually the first to leave, as I took on more clients than I could handle as a full-time college student, but there was nothing else I’d rather be doing. I remember very little about what I was designing and how many reports I’ve sent to the Framer team. I only remember the forgetting about time and sleep and sometimes friends, getting lost in redlining all my screens to make sure that they are pixel perfect so I can win another contract, or add another page to the portfolio.

Source: Redlining is something I’d spend hours doin

It’s only been a year and all the pixel-pushing have already become obsolete with the current component-driven design movement. The Framer team’s latest release on the web embodies this philosophy, abstracting away even the drawing of shapes and lines, making the carpal tunnel syndrome that I developed from the earlier days a bit of a jest.

When I was at Facebook, some senior designers complained that they no longer feel like they are crafting beautiful design, but instead, they spend all day running tests of different permutations and combinations of the lego blocks that have already been predefined by FB’s larger design systems.

This does not just happen in design or engineering, but also for company builders. Almanac is installing best practices in the workplace through docs, Notion is constructing our best life/work through templates and blocks, Landen is accelerating idea generation by quickly create/iterate on landing pages and see whether the value prop on the page can get a long list of beta testers.

The accelerating upgrading of tools that aims to automate our labor has a noble intention: to liberate us from the “annoying work” to focus on “what matters”. Most of us are well aware of this speed of change, but we don’t have enough energy or time to discuss the velocity of change, the direction that we rush towards. When we’re all so afraid to get left behind, can we really think about “what matters”?

Can’s observations are astute and painfully true:

Anyone who’s spent a few months at a sizable tech company can tell you that a lot of software seems to exist primarily because companies have hired people to write and maintain them. [...] when the times are good, people are less inclined to think of ways to fire people by automating them out of a job. Tougher times with strained margins change that calculus. But it is also partly a cognitive load issue. When you can actually remove the human from the equation, it becomes mentally easier to figure out how you could actually not write that piece of code over and over again.

I’m not sure whether the speed of automation is faster than the rate of learning or it has accelerated our learning without the need to really learn. Have we enabled creativity by reducing barriers of creation or accelerated its demise by abstracting away the lessons that we get to learn from facing the messy complexity of reality?

In “The Glass Cage”, Nicholas Carr articulates one implication of the increasingly frictionless tool:

Automation weakens the bond between tool and user not because computer-controlled systems are complex but because they ask so little of us. They hide their workings in secret code. They resist any involvement of the operator beyond the bare minimum. They discourage the development of skillfulness in their use. Automation ends up having an anesthetizing effect. We no longer feel our tools as parts of ourselves.

He goes on and asks:

[Automation] makes getting what we want easier, but it distances us from the work of knowing. As we transform ourselves into creatures of the screen, we face the same existential question that the Shushwap confronted: Does our essence still lie in what we know, or are we now content to be defined by what we want?

The long walks by the water after a day spent on the internet made me a removed observer of midwestern beauty — the pristine sky, lake blue like a gemstone, stopless angler standing. I felt like I have traveled from another dimension, so present, yet invisible. I felt like I was never a part of this tranquil and idyllic American beauty, and the path has always been one with resistance. I spent the past years trying to make a mark on screens, where pixels are the making of my version of the American dream.

There’s something liberating about recognizing that, and the realization, in some peculiar way, brought me closer to the anglers who had been standing and waiting by the water, acting without actions, fishing with no fish.

The lessons gained through the effort, through the resistance of reality, maybe as elusive as a dream. Yet the knowledge about myself, and what I’m capable of, is less ephemeral than are the practical results of hard work, like titles or money or screens. As hard work becomes more elusive, will we start rushing down the path of least resistance, even though a little resistance, a little friction, might have brought out the best in us?

That is one thing to think about as we continue to automate away.

Photo by Jimmy Baikovicius

In an interview with the Paris Review, American poet Claudia Rankine, shared the way she constructs her prose:

For me, working on a piece is like playing chess. You’re moving the language around to say to somebody, Yes, I know you’re possibly thinking this, I know this is a possible move for you. I’m going to include it here so you don’t think that I haven’t been listening. An example would be the Serena Williams essay in Citizen. That essay was dependent on the fact that a reader could go to YouTube and look up the moments I referred to in her life. I didn’t want anyone who disagreed with my take on events or remembered them differently not to have a chance to access the moments for themselves. It happened, in an interview in Boston, that a gentleman said to me, I am a real tennis fan and I don’t remember any of these things happening. The actual footage was easily obtainable by searching YouTube. I could have talked about the stress of racism on a body differently, but I needed examples that were available to the reader as raw data. I didn’t want anyone to take my word for anything.

The way language is being spoken, permeated, and interpreted has been changed with new media of transmission. The dialogues taking place in a local town hall are now broadcasted to an international stadium. Rankine’s innovation comes from being intentional about the architecture of her language. Words are no longer a writer’s artistic expression but are designed to fulfill a certain purpose.

My friend Julian gave me “Why I Write” by Goerge Orwell as a birthday gift last year. I’ve been revisiting this book in a time like this. I saw parts of myself, and every creator I know, in Orwell’s self-awareness, honesty, self-contradiction, and determination:

Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful business men […] the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

He shared five impulses that propel writers to write, and the same impulse that drives artists to create, scientists to discover, businessmen to build.

(i) Sheer egoism: Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc.

(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm: Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story.

(iii) Historical impulse: Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

(iv) Political purpose: using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after.

He openly admitted in the essay that the first three impulses largely outweighed the fourth, but we also know that he’s one of the greatest political writers ever lived, a sheer force against the narrative of totalitarianism. Despite exposing writers as a species that that’s “vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery”, he also recognized that to seek redemption, the way forward is to serve that political purpose, to push the world in a certain direction:

Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist or understand. For all one knows that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.

The “Time to Build” sentiment in tech is an inspiring narrative, but building for merely for technology’s sake is not much different from the egoistic pursuit of purple passages, sentences without meaning, and decorative adjectives.

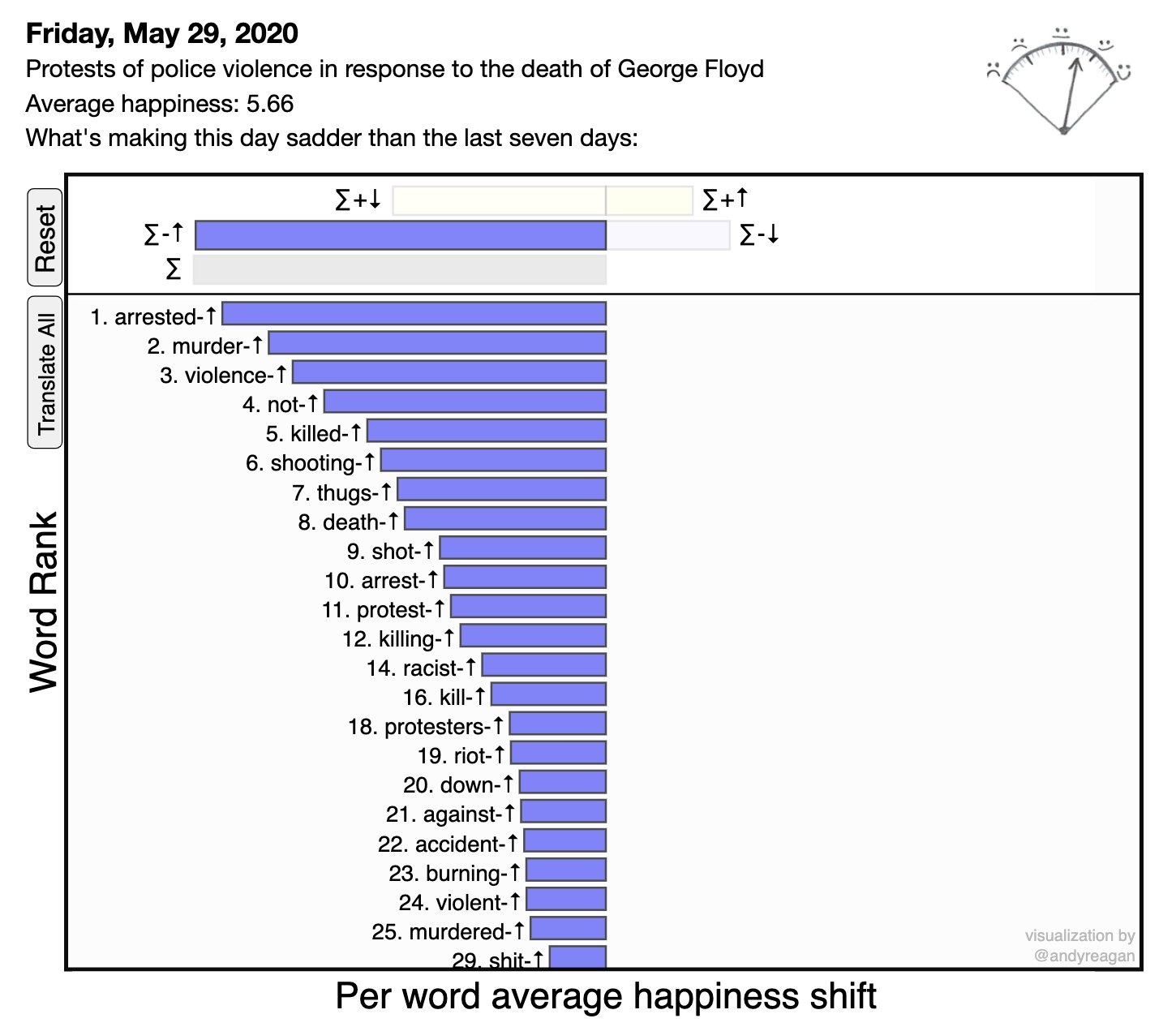

Source: Hedometer

According to Project Hedometer, yesterday was the saddest day on Twitter, the windowpane into the struggles that seem both real and unreal at the same time.

Building something seemingly mundane but useful doesn’t take much, and it’s not too late to start now.

Ways of documentation

David Lynch is releasing his 2015 short film, Fire (Pozar), online for the first time ever.

The director shared with Vice in early April that he’s hopeful people around the world will emerge from their quarantines “more spiritual” and “much kinder,” adding, “It’s going to be a different world on the other side and it’s going to be a much more intelligent world.”

In another interview, he shared the importance of intuition when rules need to be reimagined:

Now in film school, they’re teaching formulas for feature films. It’s like being put into prison. You go by intuition, and the ideas that come, and if you don’t understand them right away, just think bout them as they gather together, and something thrilling for you can come.

Lynch chose not to share much about the intention of such release. He said instead “the whole point of our experiment was that I would say nothing about my intentions”. It’s as if Lynch is flirting with the concepts of humanity and creativity in a digitally steeped world. The motif is reminiscent of Machine Hallucinations by Refik Anadol, another artist fascinated by machines’ emotional and psychological faculties.

Anadol projected images onto the walls, ceiling, and floor for an immersive viewing experience. He calls this format “latent cinema,” which he describes as “a new way of exploring narrative conceived from the mind of a machine, one that has the ability to create its own reality.”

In Melting Memories, he integrated AI with output from an electroencephalogram that measures brain wave activity, to create “ethereal abstract data sculptures visualizing the moment of remembering.”

How can we make an impact? Education and action.

When it comes to education, this guide to anti-racism has been widely circulated and is worth going through.

When it comes to action, the best thing to do is to support in a way that’s true to yourself. An example is how Adam Sandler (@NotTheFamous0ne) is offering free design services to people who need help visualizing information relating to protesting/BLM.

Few other resources:

Text “Floyd” to 55156

Fakepixels is a space for courageous thoughts.

We respect ideas, even dangerous ones. We believe in the power of deep thinking, nuanced dialogue, and creative courage.

We are a community with curious thinkers and restless builders who believe the future will be better than the status quo.

Sounds like you? Join the club and bring a friend.

Tina is a designer, writer, and investor who’s online 24/7 hunting for ideas and ventures built with grit and purpose. Born in China. Based in NYC. You can find her elsewhere on Twitter, Instagram, or a corner café.