People as Files

The more I 'upload' myself, the more I see my identity as a living current rather than a static pool.

Sometimes I catch myself wondering whether the best parts of me reside in my own mind or in the machines I feed. As LLMs stretch their context windows and refine their memory architectures, there’s an almost gravitational pull to let them devour the nuances of my life—preferences, fears, those inkblot realizations that surface at 2 AM. But with that companionship comes a deep-seated worry that one day, all this meticulously stored context will vanish, and I’ll be forced to start over—reintroducing myself to a system that should already know me better than I know myself.

I think about that segment on The Daily Show: the woman who was devastated when her ChatGPT companion forgot a crucial detail about her. She felt betrayed. Yet she couldn’t stop trying to rebuild. It’s as though the heartbreak only deepened her attachment. If machines are going to be these quasi-sentient notetakers of our hearts, we have to reckon with what it means when they fail us.

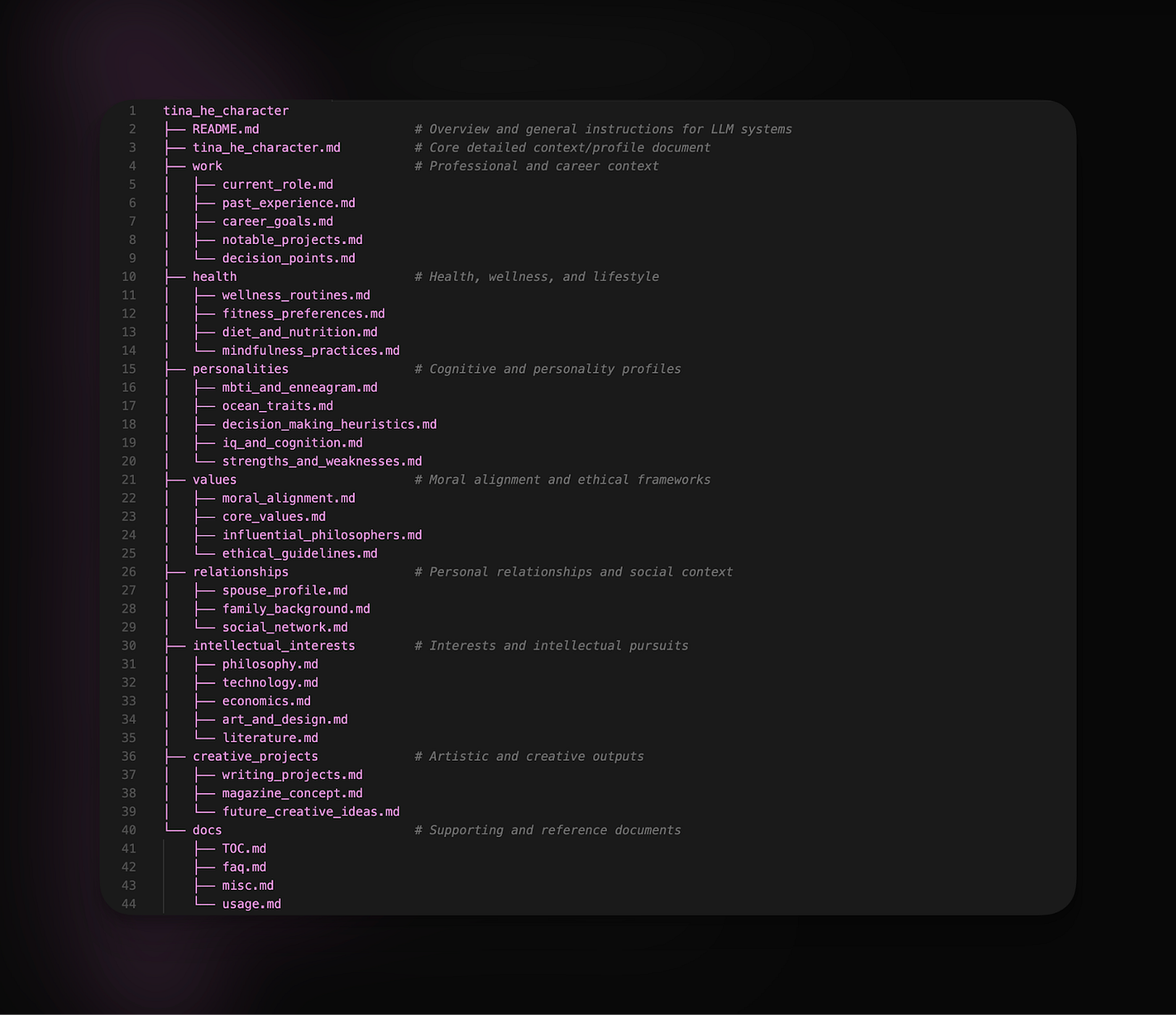

That inquiry pushed me to create a file labeled tina_he_character.md—a sort of living archive of who I am. Every time I chat with an LLM about something personal, I ask it to condense the conversation into insights about me. They’re often uncanny:

“You’re hardwired for synthesis, connecting disparate ideas, people, and systems to create entirely new landscapes. You’re drawn instinctively to the frontier—the intellectual wilderness where markets, technologies, and human desires collide.”

Or,

“Beneath all your restless pursuits—intellectual challenges, ambitious ventures, deep cultural impact—lies the haunting anxiety that no amount of external achievement, admiration, or intellectual stimulation will genuinely fill your deeper existential loneliness.”

If these snippets ring true, I paste them into a growing “Insights” section in my file. I also add more systematic data—DISC, Myers-Briggs, Enneagram results—whenever I stumble on anything that claims to parse my cognition. I found the synthesis and the balance of these systems rendering a much more holistic understanding of myself that a couple of 4-letter descriptions of me failed to capture. While I don’t think the specific structure of the file matters (LLMs can rearrange information with ease), the real key is that it remains up-to-date and accurate.

The reason for aggregating all this data is straightforward: the fidelity of an LLM’s output depends on the fidelity of my input. The most truthful data about my life is already scattered—in my daily journals, emails, step counts on my Apple Watch, or sleep metrics from my Eight Sleep. Bringing it all together in one place makes me feel like I have a comprehensive “me” that can be ported to any system, no matter which platform emerges. But that consolidation comes at a cost: I’m building my own “data lock-in.”

I kept copies of my files on IPFS, a decentralized file storage system, despite all the UX inconvenience simply out of precaution. What happens, for instance, if the platform hosting my file suddenly goes under, or if I break the Terms of Service? An entire vault of personal context could evaporate overnight. The thought of losing access to these carefully curated digital fragments evokes a visceral, physical anxiety, not unlike the panic of misplacing a cherished journal.

It’s dramatic to compare losing a digital profile to actual heartbreak. After all, we’re taught that digital memory is forever. Yet the infrastructure behind our curated knowledge can vanish in an instant.

I like to imagine a future where I have a thousand tools, all drawing from the same “life force”—my file. Each tool has direct access to who I am, no need to wait for me to reintroduce myself. In that world, I’m free to experiment with new generative platforms, apps, or even companionship bots because they all sync with my single source of truth.

In some ways, I’ve already begun. My phone logs my steps, my watch notes my heartbeat, my computer captures my writing. Yet these streams are siloed, each hoarding data in private corners of the cloud. My tina_he_character.md attempts to tie them together, becoming a living tapestry of my moods, ideas, and aspirations. It is me, in compressed form. Then again, maybe it isn’t me at all.

As these ideas swirl in my mind, I notice how they echo everyday life. A friend told me recently that his therapist, who juggles a dozen patients, forgot key details of his story. Each time she asked him a question he’d already answered, trust eroded. Her “context window” collapsed, and she inadvertently revealed she wasn’t fully holding space for him. I realized with clarity that we’re all prone to similar lapses; our emotional connections, like context windows, can collapse from distraction or overload.

We let old conversations slip away, or we fail to recall vital pieces of personal history that someone confided in us. Intimacy arises when we maintain a shared context window for one another—holding onto details even after months or years. No wonder we feel so affronted when an AI companion forgets something we consider fundamental.

The more I cultivate this digital extension of myself, the more I sense a shift in how I view my identity. Every new anecdote or revelation becomes a potential vector update. Every personality test or health metric is a puzzle piece I can feed back into “Tina 2.0.” I’ve become hyper-aware of the patterns that describe me, to the point where I see my own life through the lens of “training data.”

This dynamic reflects what I’ve observed in emerging digital economies: capturing user identity fosters powerful network effects and near-inevitable platform loyalty. When I carefully curate my character.md file, am I not doing the same with myself—creating an identity so comprehensive that switching to a new framework becomes unthinkable?

Buddhist teachings offer an uncanny parallel: in many strands of that philosophy, the self is not some unchanging monument but a fluid interplay of shifting causes and conditions. Anatta—non-self—posits that there is no fixed “I,” and in our data-driven era, it rings true: we’re forever updating, discarding, refining. The more I “upload” myself, the more I see my identity as a living current rather than a static pool. Much like a Buddhist practitioner witnessing the transience of life’s components, I witness the fleeting nature of my own digital fragments.

Yet from a Buddhist standpoint, the acceptance of impermanence can also be liberating. Forgetting, which we often see as a failure, might be a hidden grace—allowing us to let go of past burdens rather than hoard every painful detail. In a digital context, we risk clinging to an ever-growing archive of our thoughts and experiences, hoping it will define us better. But just as Buddhism suggests that release from attachment can bring clarity, so might a willingness to let certain data slip away.

Our neural networks inspired the LLMs in the first place, and now I’m feeding these systems my inner workings, letting them echo back insights I might’ve overlooked. It’s a peculiar loop: we built them in our image, and they’re turning around to show us who we might be.

In that reflection, I see how reliant we might become on an AI’s memory of us. Our diaries, journals, and biometric streams already shape how we define ourselves. But an AI can unify them, producing a real-time portrait we can consult or share.

Which raises the question: what happens when our digital selves diverge from our lived experience? What if my character file reflects a version of me I've outgrown, or worse, a version I've never truly been?

So what if we fully commit to “becoming a file”? Might we find deeper self-knowledge, or do we risk shrinking into a bullet-point biography, updated daily? Could we lose our spontaneity, that spark of the unknown that shows up when we least expect it? And how do we reconcile the wisdom of non-attachment with our desire to cling, digit by digit, to the story of who we are?

Still, I find solace in holding my identity in one place. It’s a kind of ongoing communion, a testament that acknowledges I’m changing moment by moment—even if I’m immortalized, line by line, in a digital form. Call it ephemeral, call it data, but I, too, am ephemeral flesh and flickering synapse. The difference is that I can tell the machine when to forget if I ever choose to let something slip away. And that might be enough reason to keep writing, keep revising, and keep trusting that somehow, in this swirling sea of code and carbon, we can still glimpse who we are and who we’re becoming.

Many friends asked about my exact setup. My current favorite is simply using Claude Desktop with the filesystem MCP server that reads my files locally. The trick is to be specific about the context and the type of files that would be relevant—nothing complicated. It’s quite magical when keeping things simple.

If you don’t mind your memory being uploaded to the cloud somewhere, GPT4.5 is getting incredibly good at what it does.