Twenty-five percent without thinking

We are using a supercomputer just to confirm that Paris is in France.

“Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking of them.”

— Alfred North Whitehead

I.

I was sitting in a café in SF, watching a young woman try to teach her daughter how to multiply. The child was perhaps six or seven. She was struggling with seven times eight. You could see that she was trying to get to the answer by physically exerting force and counting on her fingers, grouping invisible apples in the air, trying to derive the number fifty-six from the raw materials of the universe.

“Honey, remember? You memorized it,” the mother said gently, though she sounded a bit tired. “Don’t think about it. Just know it.”

On January 12, 2026, a research lab in China called DeepSeek released a paper that effectively said the same thing to the most powerful AI on earth.

The paper, called Conditional Memory via Scalable Lookup, makes a point that sounds technical but is actually almost philosophical. It says the Transformer, the main design behind today’s AI, is making a basic mistake. We treat it like a universal computer, making it build everything from scratch each time it responds. For example, if you ask about “Diana, Princess of Wales,” the model doesn’t just look her up. Instead, it has to create the idea of Diana from its neural network, step by step, until the answer becomes clear.

DeepSeek calls this “an expensive runtime reconstruction of a static lookup table.”

It is the architectural equivalent of the child in the café, trying to derive fifty-six by counting on her fingers every single time. It is thinking where there should be knowing.

II.

This tension between working it out and looking it up is not new. It’s been a pendulum that has been swinging since the clay tablets of Uruk.

The Babylonian astronomers did not want to calculate the positions of the planets every night. Calculation was labor intensive and required scribes, time, and the burning of oil. So they built Lookup Tables. They etched the answers into clay. If you wanted to know where Venus would be, you didn’t have to do the math, but go to the library. You traded space (clay tablets) to save time (calculation).

The history of computing has been a series of these trade-offs, each paradigm with a new form factor.

In the 1940s, memory relied on mercury and vacuum tubes, luxuries few could afford. Computers leaned on raw calculation, not storage. By the 1970s, affordable RAM let us start ‘memoizing,’ jotting things down to avoid repeating work. The 1990s brought the ‘memory wall’ as processors outpaced memory, forcing them to wait for it to catch up. To fix this, we built intricate caches—L1, L2, L3—tiny memory vaults nestled close to the processor, keeping everything humming.

The era of LLMs brought a return to pure computation. Surprisingly, this approach worked, and for a while, no one knew why. We used to want more control, but the ‘bitter lesson’ showed us that a neural network based only on logic could succeed.

Once again, constraints are driving creativity. Without access to the most expensive infrastructure ever built, Chinese engineers had to find ways to get more from their models than their American peers. These limits led them to realize that using huge amounts of GPU time to repeat facts that don’t change is very wasteful. We are using a supercomputer just to confirm that Paris is in France.

The solution DeepSeek proposes is Engram. It updates the old N-gram method, which many thought was outdated, and turns it into a fast, scalable memory. It allows the model to say: I know this pattern. I don’t need to think about it. I’ll just fetch it.

III.

To look away from the machine and towards the classroom is to see the technical error restated as a crisis of upbringing. We have presided over a quiet bifurcation of the intellect, dividing the mind into two camps in its effort to understand the architecture of the mind.

In the West, especially in elite American education, memory is often viewed with suspicion. Rote memory is seen as a weak substitute for true understanding. What matters is critical thinking: expecting children to form opinions grounded in strong logic. The strength of this approach is undeniable. It fosters a “self” that is robust against the unknown, capable of navigating terrain where no map exists. It produces the kind of elasticity that allows a mind to refuse the status quo and invent a new one.

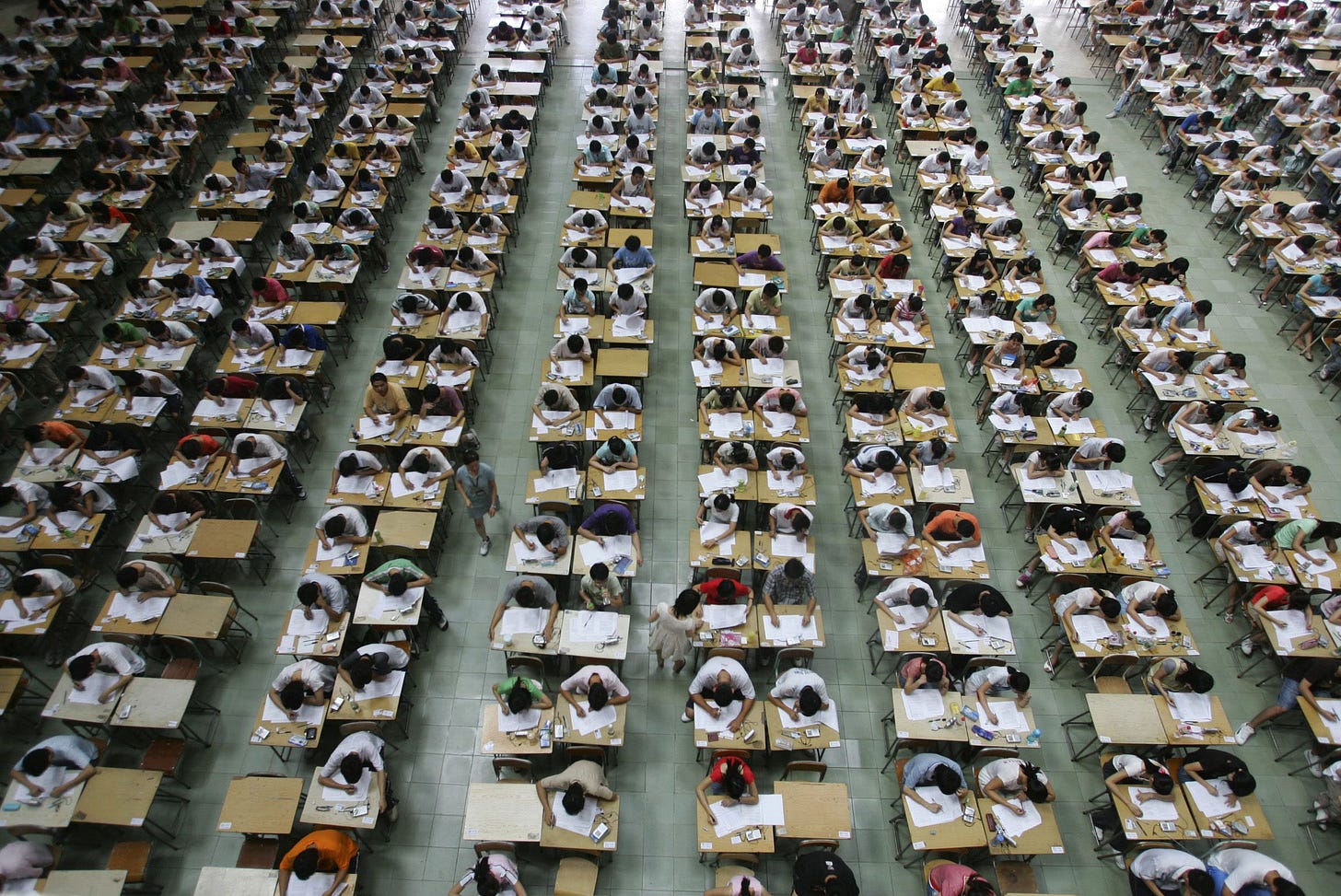

Now compare this to the approach used in places like the Gaokao, Hagwon, or the quiet evenings at a Kumon center.

Watch a child immersed in a rigorous Asian drill system, and you witness a different kind of mental machinery. This is “Pre-training” in its rawest form: the relentless, repetitive stoking of memory. These systems run on an instinct the West has mostly left behind. True fluency is a living lookup table.

The core idea here is simple: if you hammer the patterns of physics and language into memory, and rehearse the routines ten thousand times, “understanding” will eventually bubble up from the structure. Or, if you are feeling cynical, maybe understanding is just a luxury when recall is lightning-fast.

Both systems, followed to their logical ends, betray the student in different ways, leading not to mastery but to a mirrored form of paralysis.

The pathology of the ‘Eastern’ model is overfitting. The student resolves the textbook integral with mechanical perfection, yet stalls the moment the variable is disguised. They become a lookup table that has consumed its own margin for growth, dense with form, but hollow of logic. It suggests that the old critique regarding Eastern efficiency, that it excels at scale but withers at the threshold of invention, is not a mystery of culture, but the predictable consequence of a cache that has become too heavy to move.

The “Western” model, on the other hand, produces a student of dazzling conceptual agility, who can eloquently explain why multiplication works and deconstruct the colonial history of justice, but who cannot calculate the tip at a dinner party without quiet panic. They are CPUs that have overheated. They have been taught to think so critically that they have forgotten how to know.

This is why the DeepSeek paper has the quality not of an accusation, but of a startling clarification.

When engineers let the model memorize simple, everyday patterns like idioms and common phrases, the performance on reasoning tasks improved not just a bit, but a lot.

The leap in reasoning outpaced even the gains in knowledge. This exposes a truth our educational philosophies overlook: reasoning is finite, like a budget. Every second the mind spends working out the basics is a second lost from discovering how those pieces fit.

A concert pianist playing Rachmaninoff is not thinking about every note as she plays. Her performance is sustained not by conscious attention, but by its absence. If she had to stop and figure out where her fingers should go, like a student working out a math problem from scratch, the music would fall apart. She has exiled the mechanics to the darkness of habit, leaving her conscious mind free to inhabit nothing but the interpretation.

What if memorization doesn’t limit the mind, but actually sets it free? It prepares the way for real thought and originality.

IV.

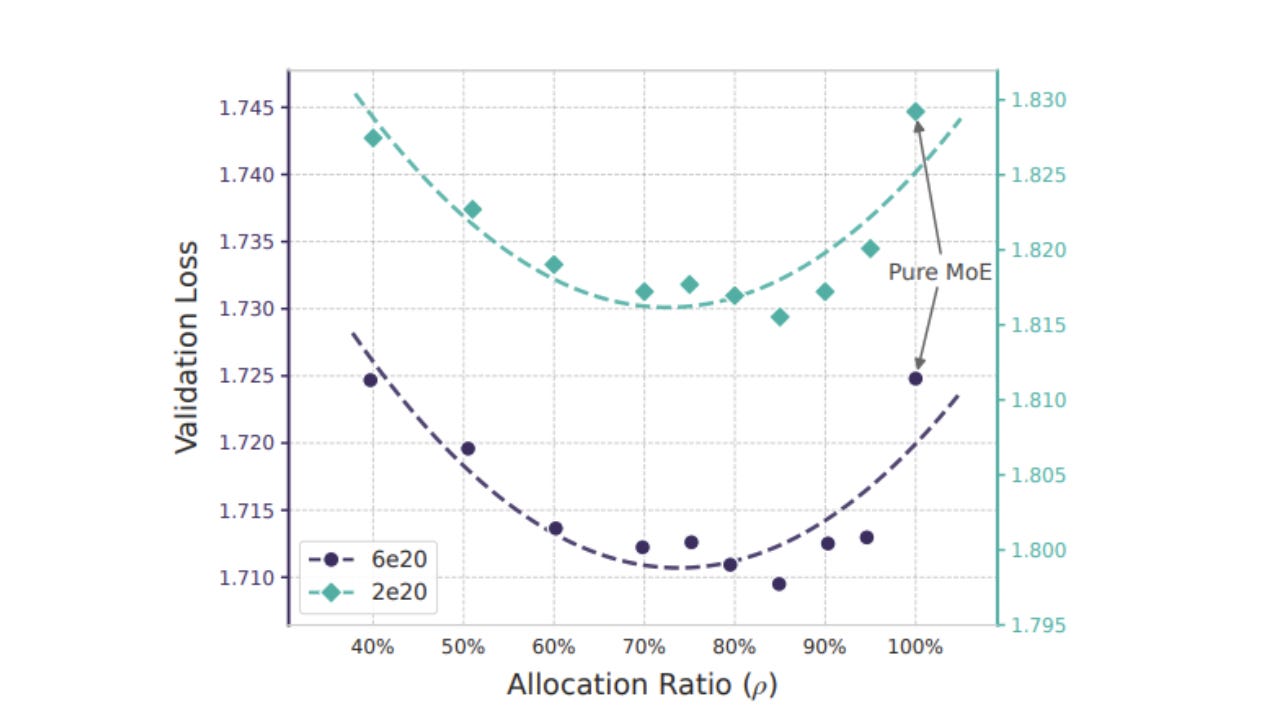

While studying the mind, DeepSeek found a pattern they called a “U-shaped curve.” They had to decide how much of the brain should be given to the “Engram,” the fixed memory store, and how much should be left for the “Experts,” the parts that handle thinking.

The findings were revealing. Without enough memory, the mind stays like a child, worn out from having to figure out everything from the beginning. But if it has too much memory, it becomes rigid in a different way. The system stops thinking because it assumes it already knows the answer.

The optimum they found was an asymmetry: twenty-five percent memory, seventy-five percent thought.

If memory goes past this limit, engineers say the model has a Hash Collision. For example, if it sees the word “Bank,” it might instantly recall a riverbank, even if the situation is about a vault. It grabs the wrong answer from memory. For people, we don’t call this a collision. We call it “experience.” Often, this is the unique problem experts face.

We’ve all met the senior partner at a law firm who has seen it all. He sits in his glass office, full of experience, and interrupts you before you finish your sentence. And most of the time he probably really does know what you’re going to ask. He basically acts like an efficient lookup table. When faced with a new problem, like a market shock or a contract issue, he doesn’t pause to think. He recognizes the pattern, remembers what worked in 1998, and uses that strategy right away.

He is fast. He is authoritative. And because the world has changed while his library has not, he is wrong. He isn’t lacking intelligence; he’s just overloaded. His mind is so full of past experiences that he can’t see what’s happening now. His recall has weakened his questioning.

The realization that vast swathes of human language should not be computed, but merely fetched, is a triumph of efficiency. But this efficiency creates a risk. A memory that cannot be refused is just a hallucination waiting to happen. This is why the memory is paired with a Gate.

The Gate stands guard between stored memories and active thinking. It’s more than just a switch; it’s designed to question what comes from memory. Its job is to catch easy answers, “best practices,” and familiar solutions, and test them carefully. It compares the comfort of past experience with what’s really happening now.

The Gate helps us distinguish between situations. It stops us from running on autopilot. It reminds us: even if this crisis looks like the Dot Com bubble and the chart looks like 1999, the details are different. Don’t rely on memory. Don’t just use old comparisons. Think it through.

V.

The DeepSeek paper asks a question that seems to be about computer chips, but it’s really about us. It’s a question of how we use our limited attention.

With only so much attention to give at any moment, how should we use it? How much should go to the parts of us that solve problems as they come up, and how much to the parts that simply remember what we already know?

Most of us are living far out on the edges of the U-shaped curve, suffering the high validation loss of a misallocated life.

I look at my friends who are under-cached. They treat every email, every social interaction, every menu choice as a novel philosophical problem. They are “principled.” They are “authentic.” They are the “Pure MoE” baseline, running hot, treating the friction of existence as a virtue. But they are exhausted. By refusing to automate the syntax of their lives, they have no depth left for the poetry. They are spending their “activated parameters” on survival.

Then there are the over-cached. These are the men and women who speak in buzzwords, who live by heuristics, who have an anecdote for everything but an insight for nothing. They have scaled their memory slots to the billions, but they have starved their reasoning. Their Gate has failed; they are no longer living, but merely re-enacting the days they have already survived.

The idea of using about twenty-five percent for memory is a guide for living thoughtfully. It means we should be careful about what we turn into habit, so we can focus on what really matters.

So, we must learn to compile.

Compile the basics. Compile the multiplication tables. Compile the polite greetings, the standard operating procedures, the route to work. Push them into the darkness of the Engram. Remove them from the critical path so you never have to think of them again.

Interpret the edges. Keep the reasoning budget holy for the moments that truly require it—the moral dilemma, the heartbreak, the crisis, the art.

“Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking of them,” Whitehead wrote.

He was right, but he was incomplete. Civilization advances by automating the operations, yes—but it survives by knowing when to turn the automation off.

The DeepSeek paper ends by celebrating a technical win: they built a machine that knows when to remember and when to think, making it a bit more efficient. But for us, seeing a child in a café finally say “fifty-six” without counting on her fingers,

It’s a reminder that we do not memorize to stop thinking. But we remember enough so that we may finally, and truly, begin.